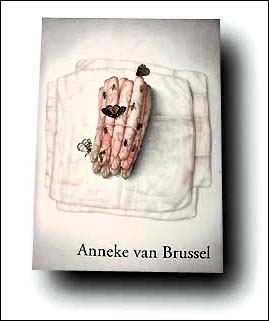

exhibition 2000 - Anneke van Brussel - catalogue

| This catalogue has been published at the occasion of Anneke van Brussel's solo exhibition, 7 October - 11 November 2000, and is compiled and written by Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pages, 28 full colour reproductions, ISBN 90-70-402-12-2) |

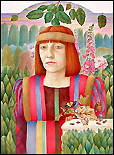

C o l l e c t e d D r e a m s

|

Collections

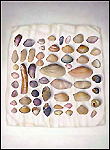

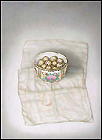

Could it be that Anneke van Brussel, with her poetic passion for collections of objects, strictly organised on some occasions but jumbled up on others, hides away in the deepest recesses of her mind the belief that by taking stock of the world, she will succeed in actually casting a spell on it? There are those who like to tell us that the human brain cannot be compared with, let alone replaced by, a computer. Even we are incapable of manufacturing it, they tell us. And then there are those who are convinced that it is only a matter of time until man will be artificially reproducible, for the simple reason that in the final analysis every one of us is composed of positive and negative charges, which we ourselves with a bit of patience and expertise could classify and arrange in the format of our choice. So, how does Anneke van Brussel see this? Of course I'll never ask her. She shows us, wordlessly proves to us that, like a caterpillar transforming into a butterfly, a straightforward and seemingly rational addition manifests itself to us, the audience, as a sense of nostalgia, poetry and secrecy - impossible to dissect, yet every bit as lucid as a dream. |

|

|

Fresh Butterflies

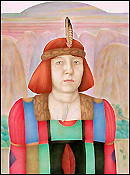

In discussions about the necessity of originality - a notion which, incidentally, is always being confused with innovation - an undertone can sometimes be heard to the effect that artists should know everything before they set to work. While writing this sentence I have decided not to entertain this idea but rather, to elaborate on the creative process itself, which is sometimes sparked by an impulse that is difficult to pin down, but can just as well be triggered by easily traceable sources of inspiration. Anneke van Brussel's work offers a wealth of clues in both respects. Many of her portraits - which incidentally invariably resemble the artist herself to a degree - derive their inspiration from the work of Piero della Francesca. Some objects I know or suspect to have played a part in her private life. The question as to whether she sees this as her contribution to the evolution of the history of art - the very question … I can just see her raise her eyebrows and hear her voice: Who, me? - is irrelevant. Several paintings forming part of this exhibition follow up on a painting by Jan van Kessel (1626-1679) featuring a number of insects. I feel (again the question remains unasked) that the artist is captivated by the atmosphere, which in Van Kessel's painting is different than wanders through our minds nowadays, and has on impulse included the very same insects in her own paintings. My answer to anyone who dares ask whether evolution is innovation or repetition is that both the origin of beauty and its consumption are processes which must be shielded from rational assessment. |

|

|

Mosquitoes and Monuments

There are no harder task masters than the sensitive, provided they know how to communicate it - on condition that we should be receptive, that is. I have experienced for myself how Anneke van Brussel, who has so much compassion for living creatures that she would neither swat nor shoo the mosquito that settles on her arm to draw blood, has been known resolutely to annihilate her tactless fellow men in the world of the written word. And yet she remains her own hardest task mistress - something which is difficult to prove, but just look at those solemn rows of sea shells, onions, beetroots, presenting themselves to us as monuments of simplicity in an atmosphere of stringently assigned sentiment. Mosquitoes and their ilk are not the only living creatures to bask in Anneke van Brussel's goodness of heart. Her allotment is an oasis of green and verdant plants, where weeds are happily left to compete with cultivated garden plants. I frequently find myself discussing the status of particular plants with her: is it a weed, or is it not? This sometimes leads to tricky situations, for many a non-cultivated plant outclasses its cultivated cousins in the dynamism department, which sometimes makes human intervention the only option. And yet even the garden is not allowed to interfere in her work. It should count itself lucky to have a single leaf or a distant tree wander into one of her paintings. As for the mosquito, it had better take care not to get stuck in the varnish … |

|

BACK