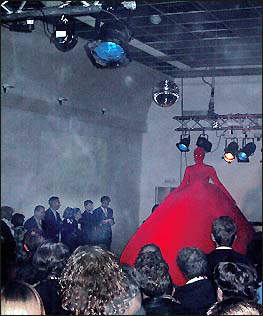

| This photograph of the Sculpture Ball, the inaugural evening of the National Gallery Weekend, does justice to neither the turnout nor the atmosphere at the time of the awards ceremony. However, if I tell you that this gathering, at which one of the participants was crowned top Dutch gallery (my congratulations to Tanya), qualified as pleasantly crowded and cautiously tolerant, surely this deserves to be called remarkable. |

| Notwithstanding the currently prevailing exultant mood, the gallery

community can look back with pride on a relatively tumultuous past

interspersed with undeclared yet fundamental differences of opinion. All art

fairs to date, you see, have somehow managed to come to nothing due to

differences of opinion on the part of the participants. This is how it

works: At first just about everyone who is anyone attends. Come year two and

although the rate of attendance reaches even higher levels, separatist

movements can be discerned at the same time. During the third or fourth year

the art fair gets bogged down due to one specific segment, claiming the

adjective "quality" for itself (what can I say - it's a word I stopped using

a long time ago), withdrawing and trying to set up an art fair of its own

where they will be spared the unpleasantness of having to work side by side

with colleagues to whose presence they object. They may even be more or less

successful in their endeavours. Two to three years later the whole cycle

starts all over again. This is how we have seen the Annual Fair come and go,

first in Utrecht (K'81, K'82 and K'83), then in the New Church for several

years, and later still at the Commodity Exchange. The exception to the rule

has been theKunstRAI, which was originally characterised by an Eastern

Bloc-like strictness which was most appositely illustrated by the

standardised and mandatory fluorescent lighting. The proponents of the

Quality Movement, who called the shots at the time, knew with extraordinary

certainty how things should be done. Nevertheless, they most commendably

managed to hang in there for a full decade until the Big Bucks eventually

took over the event, heralding the launch of the farcical Art-Amsterdam -

the very name providing the best possible proof of a major identity crisis -

which in the wake of several years of low profile messing about culminated

in these most superior beings belatedly deigning to return to the fold of

the KunstRAI, a move which they cleverly used by way of compensation to

introduce the tradition of presenting themselves with an award at the

(publicly funded) participants' cocktail party, and quite rightly so in so

far as they have to date succeeded each year in dictating the floor plan

with the threat that they might otherwise withdraw. Be this as it may, the

inaugural evening of the National Gallery Weekend was a jolly affair, at

which it took no effort at all to keep the entire audience on the edge of

their seats for a full 20 minutes by shining a torch on a white mouse

attempting to climb down a length of rope - makes sense, doesn't it, the

concept being of greater importance than the elaboration in contemporary

art, which makes a white mouse a monument of tangible substance which, most

decidedly present and highly detailed as it may be, is fortunately most

diminutive at the same time. The next day one of my visitors posed a tentative question: he and his wife regularly walked by the gallery and had always thought that everything looked so pretty and accessible, and not that things did not look pretty or accessible on this particular occasion, but what was the difference between an ordinary Saturday and this particular Saturday, which had been broadcast on a national scale with advertisements, stickers, banners, cultural sections in newspapers and so on … had they overlooked something? My client's predicament triggered an on-the-spot attack of bad conscience, and it instantly became horribly clear to me that the success of a National Gallery Weekend depends on the galleries emanating an unwelcome atmosphere throughout the rest of the year, as they evidently think they most certainly do, for what other reason could they have for devising a National Gallery Weekend in order to lure unsuspecting members of the public across their steep threshold? What I should therefore immediately see to was the replacement of my halogen lighting by fluorescent tubes. Which as such is a tradition I find most puzzling. Why is it that avant-garde is always illuminated using fluorescent lighting? In my experience this is a type of lighting which is universally seen as unfriendly and cold. But perhaps it is a reaction to the need to be different - as soon as the fluorescent tube has become a firm fixture over the wide-screen TV, the cultural trailblazers will be going for the pink lampshade. You heard it here first! There are certain cultural echelons where it is considered the done thing, or culturally correct if you like (I will henceforth abbreviate this to "TDTCC"), to adopt an uncommercial stance. I have not (yet) been able to figure out the exact meaning of this, not even within the four science-steeped walls of the grand townhouse on one of the canals which accommodates the Boekman Foundation, but that's another story. Of course I have an idea of what it could mean. In fact, I can think of several definitions with matching facial expressions, but I will personally confine myself to the following interpretation: once I have agreed with an artist that I will display his or her work to the general public, I see it as my duty to make every effort to maximise sales, and I will deploy any and all acceptable tools I can think of in the process. That's what I'm there for. If I were an unscrupulous chap, I'd resort to a regime of corporal punishment and solitary confinement as a method of coercing my artists to produce … well, something that sells well, I guess, and as the only way of finding out whether something is a hit is by selling it, I would therefore be driving my artists to repeating themselves over and over again. This is a frequently heard comment in arty circles: "he is repeating himself". And in case you have ever wondered what it means, I would suggest: he is producing more of the same, which would prompt me to conclude that the artist was simply being himself. But I digress. Of course I have the complementary argument of personal preference at my disposal, which is essential if you are to muster sufficient enthusiasm when flogging such a tricky commodity as "art" to the masses, let alone when dragging yourself out of your post-exhibition depression, having inadvertently failed to sell anything at all, but I can imagine that the TDTCC executioners will never go for this. With a little good will one could in fact accept that some unselfish souls will simply not think of hankering after filthy lucre (and aren't they worthy of our protection in a world where everything seems to revolve around money?!), but I'd say it was somewhat over the top on this basis alone to declare an entire industry to be out of bounds to activities which usually serve the peaceable purpose of securing their own survival. You should look at it from the bright side, I assured my visitors. Of course you could stress that the rest of the year will probably turn out to be a non-event, but that's not the point. You have to make a start somewhere, and this National Gallery Weekend is an example of such a Somewhere. Isn't there something glorious about such a large number of disciples of an inaccessible world forgetting to remonstrate that they are deemed to communicate their intention to lure you inside by wielding an unappetising orange banner? I think it's nothing short of wonderful, and a gesture to be much appreciated. Don't mention it even if they flog you on the spot. Bravely swallow without blinking even if they force a glass of red vinegar down your throat. You were interested in making a purchase? Just a minute, we haven't quite got to that point in the curriculum. We are currently still struggling with some internal dissension as to what to call that particular activity and embed it in life's more elevated aspects, but I have every faith that we will get there in the end. Humble Footnote This is a typically Dutch commentary. Although it is far from nice, it is nevertheless very true. I admit I could have phrased it in more subtle terms. What's more, things are not quite so gruesome in real life. The TDTCC segment does indeed comprise some truly splendid and fascinating galleries, even though it is not my impression that these are standing firm against the more dubious aspects of their collective performance. It is therefore a good idea to chronicle the recent history of the Dutch gallery community in more neutral words, albeit not in the nattering vein adopted by Truus Gubbels - yup, on the payroll of the Boekman Foundation - in her thesis entitled "Passion or Profession", an inner-circle blockbuster. Then again I should point out that Ms Gubbels also presides over the National Gallery Weekend Foundation, and so she can only mean well. |