| The Amsterdam Parking Authority has decided after due deliberation that it would be a pukkah idea to add to the attraction of parking one's car in the city, realising that it would be a jiffy to fit each central parking meter with an integrated slot machine, which they could then farm out in exchange for a cut of the proceeds, creating in one fell swoop a brilliant way of legalising fraud. I can see it all: wanna buy a parking token? Over 'ere, guv, this one works a treat, recoup your stake, win the trip of your dreams to a remote island where no-one will be allowed to drive around but you, and then there's always the poodle prize in the form of an admission ticket to the New Rijksmuseum, and what the heck, we'll toss in some frequent flyer miles while we're about it. Park yourself rich! |

|

I didn't really want to admit it, but my nerves started getting the better

of me as the afternoon progressed, that Tuesday. Debates are never

straightforward for anyone who is keen to participate. I always make the

mistake of demanding from myself that I should say the right thing at the

right time, and so I usually end up saying nothing at all, as anything I

would allow myself to say would have to be true and knock the stuffing out

of the audience, and so I invariably subject all thoughts that cross my mind

on the theme in question to the strictest of investigations, which virtually

always results in my deciding to keep mum. Leaving aside whether or not the

few comments I have been known to make satisfied these requirements, there's

always the chance of their having an unexpectedly stunning impact (I like to

look at the bright side). It was partly for this reason that I had decided

to produce copies of my various Debate Memos, which I had cleverly stapled

together in inner pocket format and had smuggled in with me. Fortunately I

managed to suppress my urges by subjecting my notes to the stuffing-knocking

test, which suddenly made me see the light: I would not be doing the

Rijksmuseum any favours by handing out my little brochures. Add to this the

fact that I am docile enough to adhere to directives issued by Debate

Supremos, this particular one having admonished us that we were not supposed

to repeat anything anyone else had already said. To be honest, I'm not so

sure this is a fair instruction to impose on people, as the frequency with

which a specific comment surfaces in the course of a debate most certainly

helps determine the overall impression.

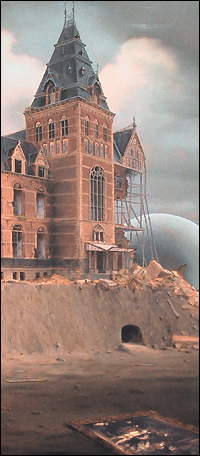

Luckily my fellow debaters ignored this instruction, repeatedly voicing the need for an explanation of what is on display at the museum, the need for putting the paintings into perspective. Having listened to various people comment on the same thing in slightly different words, I was tempted to cry out that whenever I find myself looking at a wonderful painting, I force myself to forget about its meaning: as soon as it has gripped me, it becomes my own personal story. But as it is much easier to explain the opposite, one has no choice but to let the educational swing take hold of one's brain, like the voice of a tour guide on a round-trip boat through the Amsterdam canals. And so it is purely for the sake of my love of peace that I usually end up not saying anything at all. 1. What is a national museum, and for whom is it there? 2. Is the Rijksmuseum a public facility? Is it a temple or a marketplace? And how does such a status affect a building? 3. Is the Rijksmuseum a museum on the theme of the history of art, or is it a history and art museum? 4. What is currently lacking at the museum, and what would not be missed? Now that I reconsider, I must admit that things are not quite as I had originally thought. I wish I had come up with the idea of organising the debate, but there you are. Looking into the four propositions which had been defined as the leitmotif for the debate, and which had not been communicated in advance to the hoi polloi who had merely been admitted, contrary - it was my impression - to some of the guests, who struck me as having carefully prepared for the session, one cannot deny that they largely dealt with the collection and what to do with it. In order to avoid all misunderstanding, let me put to you that there's a perfectly acceptable reason for this, in that something as mundane as accommodation should, of course, take a back seat to the contents of said accommodation. Which makes it even easier for me to put to you that I am becoming more and more convinced that this debate has been set up by way of a smoke screen, although your average citizen, who feels that he should continue to be able to cycle along the museum underpass and whose opinion on specific issues could at best be sought in the form of a referendum - an urgent tool albeit not one that Joe Bloggs is welcome to given the steep wishful thinking content of political programmes - has little say in the matter, which in turn makes you wonder why they should bother with a smoke screen at all. Remember the Mondrian-painting-as-a-gift-to-the-Dutch-people affair? Of course everyone could be dead set against it after the event, just like myself, but it remains very much to be seen whether a comprehensive and public consultation of the people would have resulted in the decision not to donate the Mondrian painting to the nation, for all actions can have the opposite effect of what they were originally aimed at, which says something for a scenario of passive tolerance. Which therefore prompts the conclusion that the plans they have for the building must be so nefarious as to make it impossible for them to imagine that the outcome of their choice could ever be attained without them resorting to machiavellian schemes. Then again, why all this negativity, even if someone has something to hide you must give them credit for their courage in risking public confrontation. And so the suggestion made by one of the last speakers, who told us to have faith in the intuitive inspirations of the architects, for everything would turn out fine if we did, struck a chord with me. It was only much later, back at the house, that I realised the missing link in this jolly appeal. You see, I can't get away from the impression that many architectural monstrosities are only recognised as such once they are in place. I can't think of any pressure group that continues the battle at this stage, in other words: no matter how ugly a building is, once it's there you don't have many remedies left to do something about it. I would therefore with the smuggest of smiles suggest to organise a public debate on the basis of a fully detailed set of scale models of the plan, subject to mandatory fatal consequences if the majority were to reject it. The question as to whether this majority is representative for the Dutch people must not be asked, as we have no way of resolving this issue. And so, barring amendment of the Constitution in favour of referendums, I could not think of any remedy which would enable the legitimacy of such a verdict to be invalidated. In fact, I'm pretty sure that such an approach would even enable the removal of the new-build structures on the Museum Meadow, but don't hold me to that. Epilogue It is the done thing in the Civilised West to contemporise old buildings (i.e., ruin fixed-up ruins) whereas the Underdeveloped Rest of the World has to date, much to our chagrin, hardly learned to appreciate its heritage. It is therefore encouraging to see that Theo Voorzaat's view has been incorporated on page 55 of the booklet with the 100 propositions on the New Rijksmuseum: "Although he is most unlikely to defend his point of view, it is for reflexive reasons as well as by way of putting incompatible viewpoints into perspective that one should be receptive to the stance adopted by the painter, Theo Voorzaat, who feels that old buildings should be given the opportunity naturally to decay, as a process that no-one should intervene in."  Detail of "Ontroerend Goed" by Theo Voorzaat |

BACK