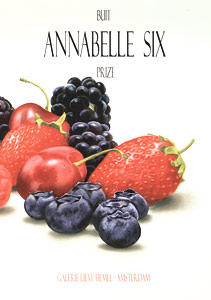

Buit

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Annabelle Six, 3-24 juni 2018, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 27 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-52-5)

Buit is een breed begrip. Alles wat een mens meer doet dan vegeteren kan leiden tot buit. Wie voldoende van het leven heeft meegemaakt, weet hoeveel voldoening buit kan schenken. In het bijzonder als het in eerste instantie niet voortspruit uit op levensonderhoud gerichte activiteiten, die overigens helaas dikwijls tot het tegendeel van buit leiden. Een zelfgekozen beroep geeft meer kans op buit dan pure broodwinning, maar alles is rekbaar. Het meest voldoening geven activiteiten, die zowel tot het domein van de vrije tijd behoren als tot serieuze professie. Met name schilderen kan zich verheugen in de belangstelling van een enthousiaste schare "vrije-tijd-besteders". Waaruit met enige regelmaat de besten naar de kroon steken van professionele collega's. Buit in zicht.

Maar natuurlijk doet het woord buit tekort aan de spirituele voldoening die schilderen kan schenken - een voldoening die het materiële aspect doorgaans overvleugelt. Al met de eerste schreden, die Annabelle Six op het magische pad van de schilderkunst zette, boorde zij een onvermoede fascinatie aan - een fascinatie die uitgroeide tot een levensdoel.

Er zijn docenten van kunstopleidingen, die het als hun taak zien stillevens te benoemen als lege hulzen van herhaling, die - zo redeneren zij - niets anders weergeven dan het kale beeld, d.w.z. zonder maatschappelijke referenties, laat staan relevantie (immers de scherpe glazuur van wat kunst heden hoort te zijn).

Wat is daarop mijn antwoord?

Het stilleven behoort tot het domein van de universele, inclusieve taal, die vele eeuwen overbrugt, dwars door politieke systemen, ideologieën, utopieën en maatschappelijke klassen heen. Het stilleven is het archetype van kunstzinnige vrijheid en tegelijk het waarschuwende symbool van - in overdrachtelijke zin - dodelijke gewoonten. Waaraan toegevoegd: niet omdat het genre in het Frans "nature morte" heet.

Hoe divers ook de gestalten zijn die het woordloze beeld kunnen aannemen, het stilleven zal er altijd onderdeel van blijven uitmaken. In het gedruis van vernieuwingsdrang en maatschappelijke relevantie is de troostende eenvoud van schoonheid ondergesneeuwd, maar niettemin onverminderd van kracht. Zoals in het maatschappelijk debat een historisch besef van (en inzicht in) de evolutie van denken en doen onmisbaar zijn, zo zijn de voorgaande eeuwen ook in beeldend opzicht onmisbaar voor het begrijpen van (en deelnemen aan) de complexe patronen die het heden over de mens uitstrooit. In feite is de durende omarming van het stilleven een teken van democratisering betreffende de acceptatie van kunst.

Maar kunst zelf is niet democratisch. Het maken, doorgaans in zijn essentie beschreven als de allerindividueelste menselijke uiting - waar ik overigens kanttekeningen bij plaats, want in zijn gedachten verkeert de mens vrijwel altijd in een staat van dialoog - onttrekt zich aan elke a priori omschreven karakteristiek, en raakt in feite de grens van singuliere autoriteit en dictatuur, maar zwiept net zo makkelijk richting brede sociale interactie. Daar dwars doorheen blijft het stilleven zich manifesteren.

Schilderen van stillevens is een vorm van het zich toe-eigenen van het geschilderde. De voorwerpen transformeren van pure aanwezigheid tot onderdeel van een emotionele entiteit. Terwijl ik dit schrijf wellen spontaan de woorden "kunstmatige intelligentie" in mij op, alsof mijn alterego mij in gedachten voorlegt dat die voorwerpen als persoonlijkheden tot leven komen, maar daar ga ik niet in mee. Ten eerste zou wat nu "kunstmatige intelligentie" heet, als "gesimuleerde intelligentie" moeten worden benoemd. Is niet het hele complex van factoren dat achter intelligentie schuil gaat, zo intens met de mens verknoopt, dat het veronderstellen van een kunstmatige variant een contradictio in terminis is? Ten tweede, wat men zo graag ziet als intelligentie van een computersysteem komt voort uit de instructies van de programmeur - de mens dus. De robot voert die uit, mits die wordt aangezet. Zelflerend is als uitdrukking minstens zo misleidend, want wat de robot ook doet, het is het regelrechte gevolg van de menselijke instructies. Algoritmes zijn in getallen vertaalde gebeurtenissen, al dan niet de mens betreffend. Die algoritmes zijn hoogstens met behulp van computers blootgelegd, een kwestie van tijdwinst dus. Het gevaar bestaat dat er te weinig mensen overblijven die begrijpen hoe de algoritmes moeten worden aangestuurd, maar met intelligentie van computers heeft dat weinig van doen.

Wat dit te maken heeft met stillevens, vraagt u zich af. Heel eenvoudig. Het onuitputtelijke reservoir van de menselijke maat omvat alle gestalten die kunst kan aannemen. Het is vreemd dat binnen de discipline van de vrije kunsten gronden van uitsluiting normaal worden gevonden. Wat nu heerst is dat op een manier, zoals gangbaar in de modewereld, het dogma van de dag leidend is. En de rest niet telt. Dat is minstens zo hard de plank misslaan als het benoemen van een berg aangestuurde elektrische stroompjes als zijnde kunstmatige intelligentie. Maar ik dwaal af.

Beter dan van transformatie is het te spreken van toevoegen van een dimensie, waarmee het betreffende voorwerp wordt verheven tot een visueel detail van de werking van de menselijke hersenen. Ik zal proberen dit te beschrijven middels het wonder van het besje. Het besje, dat je als schilder kunt herscheppen, en dat je in al zijn onaanzienlijkheid iets van de magie van ruimte en tijd kunt meegeven. Dat wonder voltrekt zich pas na een jarenlange strijd met verf en penselen, en manifesteert zich evengoed als terloops, bijna achteloos - maar dat is het niet! Het gebeurt door de eeuwen heen, steeds opnieuw, met de eenvoud van een geheime schat, omdat soms herkenning even op zich laat wachten. Wat nauwelijks deert, want wie het aangaat heeft geen uitleg nodig.

Je ziet ze op Romeinse fresco's, bij Botticelli, Jeroen Bosch, Adriaen Coorte, maar ook deze eeuw, bij Hendrick Brandtsoen, bij Peter van Poppel. Maar dit is tussen ons, hou de schilders in het ongewisse, het komt vanzelf, vroeg of laat. Het besje is eenvoudig en bij lange na het moeilijkst niet - het is zeker geen meesterproef. Of misschien toch wel. Deel van mijn fascinatie is de schijnbare achteloosheid waarmee de besjes zijn neergezet. Als schilder kun je ze pas schilderen - tussen neus en lippen door - als de hoogstandjes lukken. Zoveel eer valt er niet aan te behalen, maar ondertussen...

De mooiste zijn die waarvan het lijkt of het pigment al aan het verbleken is, maar let op, zowel de oude als de nieuwe besjes hebben min of meer dezelfde voorzichtige verzadiging van kleur, dus moet er wel opzet in het spel zijn. Ook Annabelle Six schilderde besjes, maar die zijn dominant en krachtig, en horen tot de categorie van het monumentale. Het zou best wel kunnen gebeuren... (ik acht haar ertoe in staat, maar verklap het haar niet). Terwijl ik mijn blik laat dwalen over haar schilderijen besef ik dat het een wonder mag heten dat zij in zo weinig jaren zo ver is gekomen.

|

|