|

Eeuwigheid Indachtig

|

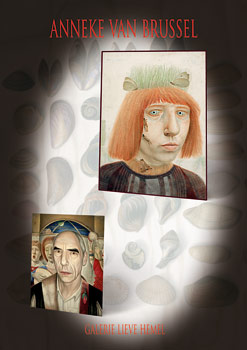

Eeuwigheid Indachtig Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Anneke van Brussel, 22 maart t/m 26 april 2020, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (20 pagina's, 59 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978 9070402 587) Een van de mooie kanten van het hebben van een galerie is dat met het voortschrijden van de tijd oude herinneringen zich aandienen in de vorm van ooit verkochte schilderijen die weer terugkomen. Meestal komen die uit erfenissen, soms ook van de oorspronkelijke koper, die door ruimtegebrek afstand moet doen van wat tot een huisgenoot is geworden. Zo kwam laatst een zelfportret van Anneke van Brussel uit 1977 tot mijn verrassing weer de galerie binnen, waardoor herinneringen aan de jaren zeventig weer boven kwamen drijven. En wat me vooral frappeerde was dat ik het nog mooier vond dan ik me ooit kan herinneren, opeens bewust van het geluk dat ik al bijna een halve eeuw met een groot schilder samenwerk. En dat niet alleen. Merk op dat insecten bij Van Brussel niet alleen een poëtische uitstraling hebben, maar ook een profetische, in die zin dat je de sprinkhanen op haar wang toch moeilijk als het summum van poëtische romantiek kunt beschouwen. Het lijkt me onwaarschijnlijk dat zij zich bewust was van de symboliek, zoals we die nu aan die inseten kunnen toeschrijven, zowel als rijke bron van eiwitten in ons voedsel, als de keerzijde waarin de natuur zo efficiënt kan voorzien, in de vorm van sprinkhanenplagen die de mensen juist hun voedsel weer ontnemen. Daarenboven komen op veel haar portretten ook rupsen, aasvliegen en engerlingen voor, voorwaar een keuze die met een eventueel misverstand over poëziealbumromantiek korte metten maakt. Dit gezegd hebbende vraag ik me af hoe ik de uitdrukking op haar gezicht in het genoemde portret moet interpreteren. Angst is het niet, dat bewijzen de sprinkhanen, die geen gevoelens van schrik of walging oproepen. Het is duidelijk dat Van Brussel haar eigen verhaal schept. Het gras op haar hoofd symboliseert de wereld zoals die zij zich wenst. Wel leest u in haar blik verwarring, of althans een onzekerheid over wat die wereld van haar verwacht, en of zij iets mag terugverwachten. Ik denk dat dit aspect een universele hoedanigheid is van kunst. De beantwoording van die vraag is vervlochten met de onzekerheid, waarmee het maken van kunst dikwijls gepaard gaat. In zekere zin heeft kunst de eigenschappen van de nog te ontwikkelen quantumcomputer, die zich kenmerkt door de onmogelijkheid dat deeltjes - misschien is het beter het woord staat of toestand te gebruiken - op twee ver van elkaar verwijderde plaatsen tegelijk zijn. Laten we niet vergeten dat we dat van gedachten en emoties heel gewoon vinden, voorzover er al verschil is tussen die twee, maar dit terzijde. De vergelijking lijkt vergezocht, maar let op, het gaat verder. Laat ik het voorlopig een gedachtenexperiment noemen, maar toch kost het u waarschijnlijk weinig moeite u voor te stellen dat kunst op een mentale wijze een opslagmedium is. Een beeld ligt dichter bij de essentie van de menselijke geest dan het woord. Het woord is een werktuig, het beeld is onderdeel van zowel stoffelijke aanwezigheid als van voorstellingsvermogen. Al formulerende raak ik ervan overtuigd dat in kunstwerken een schat aan gegevens ligt opgeslagen, die op volstrekt anachronistische wijze is vastgelegd, en dus niet alleen het heden en het verleden bevat, maar ook de toekomst. Wat in één moeite door onomstotelijk duidelijk maakt hoe belangrijk het is dat mensen vanaf hun vroegste jeugd met kunst in aanraking dienen te komen. Doen zij dat niet, zij zullen het zombiestadium nauwelijks overstijgen. Maar ik dwaal af. De onafhankelijke dwarsheid van Van Brussel is ook herkenbaar in de manier waarop ze met vergankelijkheid omgaat. Voor haar is papier een uiterst kostbaar en precair materiaal. De omringende wereld betoont zich vijandig ten opzichte daarvan. Zuurvrij papier heeft vanzichzelf het eeuwige leven, maar tegen vocht kan vrijwel geen enkel materiaal, en papier daarvan misschien nog wel het minst. Voor Van Brussel is deze verschrikkelijke dreiging van vergankelijkheid een reden om dat proces te schilderen, niet speciaal als toonbeeld van esthetiek - je kijkt er overheen of vat de strekking niet - maar zij maakte tientallen schilderijen waarop zij op deze manier dat proces van vergankelijkheid juist eeuwigheidswaarde geeft. Resten van menselijke activiteiten zijn zelden ouder dan een paar duizend jaar, terwijl de homo erectus toch al 1,9 miljoen jaar geleden op aarde rondliep. Het enige dat de tand des tijds heeft doorstaan, op een hoogst zeldzaam botje na, zijn de vuurstenen werktuigen. Hoe mooi is het niet dat Van Brussel een proces van ontbinding ombuigt naar een bezwering van het tegendeel, als een ode aan de eeuwigheid. Dat zij vergankelijkheid als onverwoestbare beschadiging van het menselijk tekort, als door een dubbele negatie transformeert tot schoonheid en balans in plaats van koorts en verloren dromen. Ook op andere wijze jongleert Van Brussel met het onbereikbare perspectief van eeuwigheid. In reeksen schilderijen citeert zij uit het werk van Piero della Francesca, Memling en Mantegna, om er een paar te noemen. Dat doet zij natuurlijk in de eerste plaats omdat hun werk haar insipreert, maar als bijvangst voorziet zij in extra pijlertjes onder de brug die de geschiedschrijving tussen het verleden en de toekomst slaat. Het hoeft niet alijd een naam te hebben. Let op de bescheiden, maar toch duidelijke rol die onaanzienlijke voorwerpen als schelpen spelen, die na hun eerste kortstondige leven als bescherming voor weekdieren, vele eeuwen trotseren, slechts gedwarsboomd door de eindeloze beweging van golven, die sliijpen en beuken tot het bittere einde, hoewel deze woordkeuze niet voor rekening van het heelal komt. Voor wie het ziet, niet voor het eerst valt die mengeling van kinderlijk perspectief en zwaarmoedig eeuwigheidsbeleven op. Ook in de fotoalbumseries en zelfs in de voor haar atypische reeks van het IJ in de mist klinkt dit beleven door. Zelfs haar vriendschappelijke relatie met Ramses Shaffy, die zijn liederen ruim doseerde met weemoed en verlangen, past in dit stramien, wat hem op vereeuwiging in de vorm van meerdere portretten kwam te staan. Niet onvermeld mag blijven dat ik mij in mijn ijdelheid gestreeld voel omdat Anneke van Brussel meerdere keren mijn rare hoofd heeft geschilderd. Maar dat het op de omslag terecht is gekomen heeft een andere reden. Het hier al genoemde zelfportret uit 1977 inspireerde mij tot de tekst van deze catalogus en bovendien beschouw ik mijzelf als een exponent van de buitenwereld waarmee zij in aanraking kwam. Ik kijk, door haar toedoen, gelukkig streng, zodoende klopt mijn verhaal min of meer. Maar u moet weten dat ze mij veel strenger laat kijken, veel manhaftiger dan ik ben. Ik ben een twijfelaar, ik luister naar alles, ik vraag me af - nee, bevragen, daar doe doe ik niet aan, dat vind ik een raar woord - ik vraag me gewoon van alles en nog wat af. Dat proces gaat continu door, altijd al. Dat portret flatteert mij, het is niet anders. Als u mij kent dan weet u dat ik, als ik voor een microfoon voor de vuist weg spreek, heel dikwijls eh eh eh zeg, dat ik zinnen opnieuw begin, de werkwoordsvormen verhaspel, dat ik niet op een woord kan komen, er iets gammels voor in de plaats zet, kortom, dat portret maakt het mooier dan het is. Niettemin vind ik het natuurlijk fantastisch dat ze van een laatbloeier nog een overtuigende kop kan maken. Niet alleen voor de eer met haar kunst te mogen werken, ook daar ben ik Anneke dankbaar voor. In Tribute to Everlastingness

One of the perks of running my own art gallery, I have found, is that it enables me to relive past memories whenever a painting I sold at one time finds its way back to me, either because the owner’s deceased estate is having to be wound up or because the original buyer as part of a downsizing exercise has had to bid farewell to what over the years has become a trusted companion. When not long ago, completely out of the blue, a 1977 self-portrait by Anneke van Brussel winged its way to the gallery, in addition to the unexpected reunion sparking all kinds of memories of the 1970s in me I actually – to my considerable surprise – found myself admiring the painting even more than I could remember ever having done, in the sudden realisation of having been fortunate enough to have clocked up almost a half century of collaboration with an artist of such supreme stature. But that’s only the half of it. Anneke van Brussel’s insects, it’s important to appreciate, in addition to being shrouded in poetry also convey something prophetic, in that it’s hardly possible to regard the cicadas the artist has depicted on her cheek as the summum of lyrical romanticism. I doubt that the artist herself was aware, back in the day, of the symbolism we have since come to ascribe to insects like this, not just as a valuable source of protein in our diet, but also as the other side of the coin Mother Nature doles out with such devastating adeptness whenever she inflicts a locust plague on the human community, thereby depriving all of mankind of its food. And let’s not forget the caterpillars, bottle flies and June bug larvae that feature in so many of her portraits, as a choice that couldn’t give shorter shrift to a possible misunderstanding about the romanticism of the primary school friendship album. At which stage of the proceedings I cannot help wondering how to interpret the expression on the artist’s face. Fearfulness it cannot be, for the cicadas surely do not spark sensations of fear or disgust. Clearly Anneke van Brussel shapes her own story. The grass on top of her head is a symbol of her preferred world. There is an element of confusion to her gaze, or perhaps it is merely a degree of uncertainty about the world’s expectations of her and whether she would be justified in entertaining expectations of her own. I think that this aspect is one of the universal qualities of art. Answering the question is inseparable from the uncertainty that more often than not is such a staunch presence whenever art is being created. Art in a sense has the qualities of the quantum computer whose development is yet to be completed, and which will be characterised by the impossibility of individual particles – or perhaps it would be better to use the word “status” or “condition” – being situated at any one time in two different locations. Far-fetched as this comparison may seem, this is not nearly the end of it. Let’s for now refer to it as a thought experiment, but you will in any event find it quite easy to imagine that cognitively speaking art is in essence a storage medium. Images correspond more closely with the essence of the human spirit than words. The word is a tool, whereas the image is part of material presence and imagination at the same time. My conviction grows as I am carefully piecing together these words that works of art accommodate a host of information filed in an utterly anachronistic manner which in addition to the present and the past also extends to include the future. Which in one fell swoop makes it unequivocally clear how important it is for people to come into contact with art at the earliest possible age, under pain of their ending up all but unable to transcend the zombie stage. But I digress. Anneke van Brussel’s free-spirited intractability is also reflected in her way of dealing with the ephemeral. In her world paper is a most precious and precarious material which the surrounding world treats with resentment. Although acid-free paper per se should last forever, its resistance to moisture – the enemy of most if not all materials – places it at the very bottom of the league. It is this abysmal threat of transience which inspires Anneke van Brussel to paint the very process, not particularly as a prototype of aesthetics (you either overlook it altogether or fail to appreciate what it means), but she has made dozens of paintings in which she has used this technique to superimpose an element of the eternal onto the process of transience. Although it has been established that homo erectus walked the earth some 1.9 million years ago, remnants of human activity tend only rarely to date back more than a few thousand years. The only objects that have survived forever – not counting the occasional super rare piece of bone, that is – have been flint tools. Which makes it all the more enchanting to observe how Anneke van Brussel reshapes the process of decomposition into an incantation of the exact opposite, as an ode to eternity, by using her version of the double negative to transform transience as an indestructible disfigurement of human failure into exquisiteness and equilibrium rather than frenzy and broken dreams. That Anneke van Brussel is a consummate juggler of the elusive perspective of everlastingness is reflected among other things in the series of paintings in which she has paraphrased the legacy of Pierro della Francesca, Hans Memling and Andrea Mantegna, to name but a few – not only because she has always drawn so much of her inspiration from their works, but also as a sophisticated way of adding the occasional extra pillar to help prop up the bridge that connects the past and the future. That it isn’t always necessary to label it is borne out, for example, by the discreet yet unambiguous contribution made by trivial objects such as the humble sea shell, which after a fleeting existence as a cuirass for its resident mollusc can endure for many more centuries, battered by the ocean’s never-ending waves that crush and pound until the bitter end, although it isn’t the universe that can be credited for this particular choice of words. It is not for the first time, for those who see it, that the artist’s mix of naïve perspective and forlorn eternity experience has come to the fore: her photo album series and even her series of paintings – in marked departure from her trademark approach – of the IJ waterfront, thick with fog, echo the same sentiment. Even her friendly relationship with Ramses Shaffy, whose songs were always laden with melancholy and longing, fits into this pattern, which earned him the accolade of being immortalised in several portraits. Tlthough I cannot deny having had my vanity tickled by Anneke van Brussel’s various renditions over time of my quirky noggin, that is not why one of her portraits of me has appeared on the front cover. It was the artist’s self-portrait from 1977 which inspired me to write the text for this catalogue, in addition to which I consider myself as an exponent of the outside world with which she came into contact. She has painted me with a stern expression on my face, which is quite fortunate as it backs up my story. You should know, however, that she has made me look considerably more austere and bold-faced than I really am. I am a doubter, I listen to everyone and everything, and no, in case you wonder, I am not the querying type, I simply cannot stop wondering, as a non-stop part of my life I cannot remember ever having been without. It cannot be denied that the artist has painted me in a flattering way. Anyone who has ever met me knows that I say “um” and “er” a lot when speaking off the cuff into a microphone, that I keep having to start over because I tend to flub my lines, that I mangle my verbs and that I sometimes cannot find the right word at the right time and end up using a lame alternative. My portrait, in short, has made everything look better than it really is. Even so I am in awe of her ability to depict such a late bloomer as myself so convincingly. In addition to the privilege of working with the art she creates, this too is something I owe Anneke a debt of gratitude for. |

|

TOP