VORMENTAAL (I)

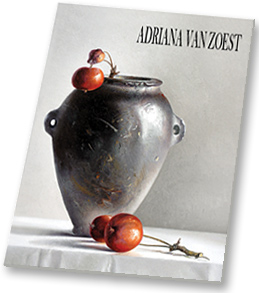

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Adriana van Zoest, 8 september t/m 6 oktober 2007, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 28 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978 90 70402 204)

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Adriana van Zoest, 8 september t/m 6 oktober 2007, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 28 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978 90 70402 204)

Het verleden, het moment zelf, de toekomst, bijna alle daden en bedoelingen spelen zich af in deze drie niet te scheiden perspectieven. Wie terugblikt kleurt zijn geheugen met alle ervaringen tot nu toe, dus wie mijmert bij een carrière van 25 jaar als schilder voelt en ruikt al aan de toekomst. Onzeker of niet, de grote lijnen zijn er, het bestaan van verwachtingen, al dan niet uitgesproken, heeft niet eens een bewijs nodig. Het niet te temperen enthousiasme van Adriana van Zoest roept als vanzelf de reactie van "nu al?" op, want het vieren van een jubileum gaat voor dat je het weet lijken op een afronding, en dat is nu juist het laatste waar zij aan denkt. Maar die met schilderen gevulde 25 jaren zijn er wel degelijk, en hoewel deze tentoonstelling absoluut geen terugblik is, reik ik u met deze woorden een moment van mijmering aan, waarbij u even stil kunt staan bij wat u in de afgelopen jaren van haar hebt gezien, in één moeite door de huidige collectie op u in laten werken, en u verheugen op wat nog komen gaat...

Nog niet zo lang geleden heb ik met enige hardnekkigheid geprobeerd de verschillen tussen het stilleven uit zeventiende eeuw en het heden te karakteriseren. De tijdspanne lijkt overdreven groot, maar niet alle ontwikkelingen gaan langs revolutionaire paden. Ik zou bijna zeggen, dat klinkt weer als een open deur, maar sinds alles vernieuwd moet worden, kon het wel eens zijn dat u verrast opkijkt, maar dit terzijde. Ik had het over pronkzucht die plaats heeft gemaakt voor soberheid. Voor sommige schilders, zoals Olav Cleofas van Overbeek en Ben Snijders, gaat dat zeker op, maar zo eenduidig als een theorie is de schilderkunstige praktijk niet. Kortom, ik herondekte het betrekkelijke van een schoonheidsideaal. Als een sober voorwerp op een schilderij u en mij tot tot een weldadige schoonheidsbeleving brengt, dan is er ook een vorm van pronken in het geding. Willen wij niet laten zien dat onze ingewikkelde geesten ook een essentieële beleving kunnen ontlenen aan iets eenvoudigs? En bedoelen wij daar niet onuitgesproken mee dat wij dan weer een stapje verder zijn?

In sommige schilderijen van Adriana ligt het nog weer anders. We volgen haar in gedachten op haar rondgang langs de Nederlandse veilingen en zien haar daar bieden op voorwerpen, die zij selecteert op tot haar verbeelding sprekende vorm. Naar meestal pas achteraf blijkt, dragen die dikwijls een opmerkelijk verhaal met zich mee. Dat kan een vaas van Copier zijn, een oude Egyptische balsemvaas (pagina 7 en 11) – die als ongedecoreerd gebruiksvoorwerp wonderwel de verschuiving van praal naar soberheid illustreert, zij het dat de timing even ontspoort – of een los van elkaar verworven setje keramische voorwerpen van “Onder den Sint Maarten” (zie pagina 13). Deze voorwerpen werden begin twintigste eeuw gemaakt, mede onder invloed van het toen dominante Art Deco, in een klein atelier van die naam, dat was gevestigd in Zaltbommel. Het lijkt wel of ook voorwerpen zich lenen voor morfische resonantie (met dank aan Rupert Sheldrake). Maar waar het om gaat, Adriana zoekt voorwerpen die in haar ogen schoonheid in zich bergen, al kan het zijn dat pas in het stilleven zelf die beleving zich openbaart.

FORM LANGUAGE

This catalogue has been published at the occasion of Adriana van Zoest's solo exhibition, September 8 - 6 October 2007, and is compiled and written by Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pages, 28 full colour reproductions, ISBN 978 90 70402 204)

This catalogue has been published at the occasion of Adriana van Zoest's solo exhibition, September 8 - 6 October 2007, and is compiled and written by Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pages, 28 full colour reproductions, ISBN 978 90 70402 204)

Present, past, future: three inseparable perspectives within which virtually all acts and intentions are played out. As retrospection tinges one’s memory with the full complement of experiences to date, so does reflection on a painting career spanning a quarter of a century involve a foretaste, a whiff of things to come. Undecided or not, the outlines are all there, the existence of expectations – undeclared as some of them may be for now – not even needing any substantiation. Adriana van Zoest’s irrepressible gusto naturally evokes a response of “Has it really been that long?”: before you know it, celebrating an anniversary takes on something of a rounding off exercise, and rounding off is the last thing on her mind. Nevertheless her 25 years of painting are very much in evidence, and although this exhibition is anything but a retrospective, these few words of mine are intended to present you with a moment of contemplation, for you to recall those of her works you have seen over the past years, take in the current body of work while you are about it, and relish in what is yet to come …

It wasn’t that long ago that I had a determined stab at pinpointing the differences between still-lifes from the seventeenth century and their contemporary counterparts. Although the time frame may seem inordinately large, it should be borne in mind that not all developments travel along revolutionary paths. “Stating the obvious” is what I’d be tempted to call this, but as innovation is the name of the game, you yourself could well end up surprised – but never mind all this for the moment. What I was writing about was ostentation having given way to restraint. Although this is most definitely true of some painters, such as Olav Cleofas van Overbeek and Ben Snijders, the practice of painting is not as straightforward as a paradigm would be. In short, I rediscovered the relativity of the ideal of beauty. If an austere object in a painting evokes an uplifting sense of beauty within you and me, then that too involves something ostentatious. Are we not keen to demonstrate that our complex minds can also derive an essential experience from something straightforward, and in doing so, are we not tacitly hinting at having scaled yet another rung on the ladder?

Things are different still in some of Adriana’s paintings: in our minds we follow her while she is doing the rounds of the Dutch auction houses, where we see her bidding for objects she has selected for the appeal to her imagination of their form. Most of them are subsequently shown to come with a particular tale of their own, such as the glass vase by Copier, the ancient Egyptian embalming jar (see pages 7 and 11) – which as a plain utensil represents a perfect example of the shift from ostentation to restraint even though the timing could be said to be slightly off – or the group of ceramics (each of them independently acquired) marked “Onder den Sint Maarten” (see page 13). (“Onder den Sint Maarten” was the name of the Art Nouveau furniture and brassware studio which operated circa 1900 in the picturesque Dutch town of Zaltbommel, just south of the river Waal, and which had taken its name from the fact that it was located at the foot of Saint Martin’s bell-tower.) It is as if objects too lend themselves to morphic resonance (courtesy of Rupert Sheldrake). But what matters is that Adriana looks for objects which she recognises as being things of beauty, even though it may require the context of the actual still-life to allow this to be revealed.

|

|