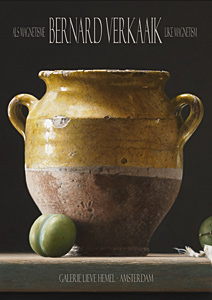

Als Magnetisme

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Bernard Verkaaik, 11 mei t/m 8 juni 2013, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 16 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-41-9)

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Bernard Verkaaik, 11 mei t/m 8 juni 2013, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 16 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-41-9)

De eeuwige vraag over de bedoeling die een schilder met zijn werk heeft, is bij een stilleven wat weggëbt, maar is onverwacht toch weer prangend geworden sinds de lancering van de kreet Conceptueel Realisme, want zegt u nou zelf, wie kan daar tegenop. Maar we zullen ze eens een poepje laten ruiken.

Een korte typering van het werk van Bernard Verkaaik zou kunnen gaan over de eerbiedige aandacht voor sobere, niet primair decoratieve en dikwijks robuuste gebruiksvoorwerpen, in symbiose met vruchten en groenten, soms een enkel een bloempje. Het lijkt alsof de reclameman van vroeger zich tot het uiterste concentreert om in een gemoedstemming te komen, waarin het behagen en verleiden van de consument is uitgebannen, waarin de modus van de geest is teruggezet naar de basisbehoeften, waarbij als enige vorm van opsmuk, en dan nog ternauwernood, het licht is, dat zwerft op en rond de dingen en de vruchten. Die schoonheid is er altijd geweest en zal er altijd zijn, zoals een berg ook zonder onze ogen majestueus is, maar moet steeds opnieuw worden ontdekt. Althans, het is de mens zelf die zijn eindigheid relativeert door het steeds opnieuw ontdekken en uitdrukken van schoonheid als een bewijs van originaliteit en eeuwigheidswaarde te beschouwen. Het lijkt wel of Verkaaik ook dat tot een minimum probeert te beperken door onevenredig veel aandacht te schenken aan stof, roest, beschadigingen en scherven, ontbrekende wel te verstaan.

Schoonheidsbeleving van kunst is tegelijk hoofdzaak en bijzaak. Waar het om gaat is het invoelbaar worden van subjectiviteit, voortvloeiend uit de onmogelijkheid om kwaliteitscriteria te formuleren die worden begrepen en onderschreven.

Een belangrijke barrière bestaat evenwel daaruit dat vooral deskundigen weigeren toe te geven dat hun maatstaven onderhevig zijn aan diezelfde subjectieve krachten. Het nadeel daarvan is dat ieder, die alsnog probeert tot een hanteerbare formulering te komen, niet anders kan dan constateren dat alle kunst de potentie van genialiteit in zich draagt, wat natuurlijk niet zo is, maar vooralsnog de beste oplossing is na het bewijs uit het ongerijmde. Zolang het taboe van de menselijke feilbaarheid van kunstenaars in stand wordt gehouden blijft frustratie en venijn bij deskundigen en leken de boventoon voeren. Maar daarover een andere keer. In termen van filosofie is het zinvol de betekenis van het woord bewustzijn opnieuw te formuleren, onder meer door implementering van opzet versus onmacht, met subjectiviteit als zwevende constante.

Er valt wat voor te zeggen dat belangstelling voor kunst ontstaat als ruimschoots aan de eerste levensbehoeften is voldaan. Dat loopt niet synchroon met de opvoedende waarde die men kunst toedicht, tenzij bewezen kan worden dat kunst het vermogen te voorzien in eerste levensbehoeften stimuleert. Precies, de kip of het ei. Bij nader inzien kan het lemma eerste levensbehoeften beter worden vervangen door de behoefte aan intellectuele prikkeling, waarbij toch weer de gedachte opkomt dat pas boven een bepaald niveau van geestelijke ontwikkeling die prikkeling verband houdt met het subtiele van kunst, en meer in het algemeen met abstract denken.

En de behoefte dan, hoe zou die zijn te formuleren? Is het zo eenvoudig dat je kunt stellen dat stillevens de menselijke geest rust geven, de kans bieden om te ontspannen in die kakafonie van gebeurtenissen en invloeden? In het besef dat een volledige inventarisatie vooralsnog een illusie is en afleidt van waar het hier om gaat, lijkt het me verstandiger te volstaan met dit voorbeeld van de impact van stillevens.

Of zou onze geest, niet in te tomen wat onophoudelijk voortijlende gedachten betreft, graag geleid worden, hoe onuitlegbaar het schilderij waarnaar wij staren ook is? Het beeld van koortsige spiralen van beelden en indrukken, die getrimd worden, gejusteerd, geordend, steeds opnieuw, door het onherroepelijke van het raadselachtige beeld waarnaar wij kijken. Dat werkt als een constante van aangereikte stabiliteit, waarop steeds weer alle levensvragen geprojecteerd mogen worden, zonder de wanhoop van hun uitkomstloosheid.

Terug naar Verkaaik. Is het waar dat de tegenhanger van maatschappelijk succes en optimaal rendement zich voordoet als diep verlangen naar stilte en mentaal evenwicht? Deze vraag lijkt gesteld vanuit het gezichtspunt van de toeschouwer, maar toch gloort daarin ook het rudimentair streven van de schilder Bernard Verkaaik. Verkaaik namelijk weet uit eigen ervaring - ooit was hij succesvol reclameontwerper - hoe verweven dienstbaarheid is met het juist niet vervullen van dat diepe verlangen naar stilte. Wat hij wel wil loopt parallel met de zoektocht van de toeschouwer, maar het verschil is dat hij het doet vanuit zijn eigen wens en perspectief, en niet om alsnog de toeschouwer te dienen, zeg maar te behagen, hoe goed hem dat uiteindelijk toch lukt.

Deze met devote precisie geschilderde stillevens voeren de toeschouwer als het ware de cel van een contemplerende monnik binnen, terwijl zich tegelijk een weids landschap vol stilte ontvouwt. Dat hangt nauw samen met het prachtige bescheiden, maar geconcentreerde licht, dat Verkaaik door de afgekaderde ruimte van het stilleven laat zwerven, ongrijpbaar, maar, zoals de voorwerpen, bijna aanraakbaar. Onuitlegbaar? Welnee, dat licht slaat een brug tussen de sensitiviteit van de schilder en die van de toeschouwer. Zoals ijzeratomen door een magneet geordend worden, zo brengen de schilderijen van Verkaaik rust en ordening in de chaos van onze geesten, en, om de metafoor nog verder uit te benen in een ultieme poging het ene beeld met het andere te verklaren, trekken die onweerstaanbaar onze blikken naar zich toe.

Like Magnetism

This catalogue has been published at the occasion of Bernard Verkaaik's solo exhibition, May 11 - June 8, 2013, and is compiled and written by Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pages, 16 full colour reproductions, ISBN 978-90-70402-41-9)

This catalogue has been published at the occasion of Bernard Verkaaik's solo exhibition, May 11 - June 8, 2013, and is compiled and written by Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pages, 16 full colour reproductions, ISBN 978-90-70402-41-9)

Having gradually abated to a degree where the still life was concerned, in recent times the everlasting question as to the painter’s intention of the works he creates has unexpectedly regained its original acuteness owing to the launch of the phrase “conceptual realism”. I'm sure you'll agree that it would be hard at the best of times to top this, but let's give them a run for their money anyway!

For a start, a succinct characterisation of Bernard Verkaaik’s work could discuss the artist’s deferential attention to sober, non-primary and often robust utensils in a symbiosis with fruits and vegetables or, occasionally, the merest diminutive flower. It is as if yesteryear’s advertising executive is now concentrating with all his might on achieving a mood from which kowtowing to the consumer and tempting him or her has been banished, in which the mode of the spirit has been returned to the basic requirements featuring as the sole form of embellishment – and barely, at that – the light drifting over and around the objects and the fruits. Although this splendour has always existed and will always exist, in much the same way that a mountain is equally magnificent without us actually seeing it, time and again it needs to be rediscovered, or rather, it is man himself who puts his own finiteness into perspective by deriving a sense of originality and eternity from the continual rediscovery and representation of beauty. This too, it seems, is something that Verkaaik tries to trim down to the barest minimum by devoting disproportionate attention to grime, rust, nicks and shards – those that are no longer there, to be sure.

Experiencing the beauty of art is imperative and inconsequential at the same time. What matters is that subjectivity should be rendered recognisable as a corollary of the impossibility of formulating quality criteria that meet with appreciation and endorsement. However, a major impediment is that experts in particular refuse to admit that the criteria they wield are subject to these very subjective forces. This has as a drawback that anyone who attempts all the same to arrive at a usable formulation cannot but come to the conclusion that all art harbours the potential of genius, which clearly cannot be right, but which for now as a solution represents the next best thing to indirect proof. As long as the taboo of the human fallibility of artists is preserved, frustration and malice will continue to reign supreme among experts and laymen alike – but let’s discuss that another time. Philosophically speaking it is helpful to reformulate the meaning of the word consciousness, among other things by implementing intent versus incapacity, with subjectivity as a floating constant.

There is something to be said for the view that an interest in art is generated once the bare necessities of life have amply been met. There is no synchronicity here with the educational value that tends to be attributed to art, unless it can be demonstrated that art furthers the ability to meet the bare necessities of life – a chicken and egg scenario if ever there was one. On second thought it would be preferable to replace “bare necessities of life” as a catch phrase with the need for intellectual stimulation, which, like it or not, sparks the consideration that it is not until a particular level of spiritual development has been achieved that this intellectual stimulation assumes an association with artistic subtlety and, more generally, abstract thought.

So how about formulating the requirement itself? Is it so straightforward as to warrant the suggestion that still lifes soothe the human mind and enable it to unwind amidst the cacophony of incidents and influences? Knowing full well that a comprehensive fledged inventory would as yet be an illusion, not to mention a distraction from the crux of the argument, I would recommend that we make do for now with this example of the impact of still lifes. Or does our mind with its incessantly rambling thoughts prefers being shown the way no matter how perplexed we are by the painting at which we find ourselves staring? The image of feverishly swirling images and impressions that are trimmed and tweaked and rearranged, again and again, by the irrevocability of the mysterious image we are looking at, operates as a constant of supplied stability onto which the full range of questions of life may be projected without the despondency of their futility.

Back to Verkaaik. Is it true that the counterpart of social success and optimum return manifests itself as an intense yearning for serenity and mental poise? Although this question appears to have been raised from the spectator’s perspective, at the same time it contains a glimmer of the rudimentary aspiration of Bernard Verkaaik as a painter, whose own experience – as the acclaimed commercial designer he once was – has taught him how closely intertwined the pursuit of social success is with not giving in to this deep craving for tranquillity. What he does seek to achieve runs parallel to the spectator’s quest, albeit that the artist is spurred on by his own desire and perspective rather than by a wish to attend to his audience to the point of delighting them, even though this is exactly what he ends up doing so very well.

These still lifes, created as they have been with devout precision, in a manner of speaking lead the spectator into a contemplating monk’s cell while a panoramic landscape steeped in silence unfolds at the same time. There is a close association with the gloriously modest yet concentrated light which Verkaaik has drifting throughout the defined area occupied by the still life, impalpably yet all but tangibly, like the objects shown. Does it defy explanation? On the contrary: the light bridges the gap between the painter’s perceptiveness and that of the spectator. In much the same way that a magnet causes iron atoms to rearrange themselves, Verkaaik’s paintings instil a sense of tranquillity and order in the chaos of our minds and, to labour the metaphor even more, in a last-ditch effort to explain one image by using the other, compellingly entice our gaze.

|

|