Persoonlijk Universum

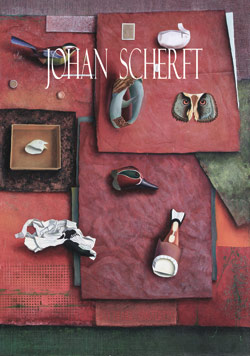

Deze catalogus is verschenen ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling van Johan Scherft, 1-22 juli 2018, en is samengesteld en geschreven door Koen Nieuwendijk. (16 pagina's, 33 afbeeldingen in kleur, ISBN 978-90-70402-53-3)

Het werk van Johan Scherft (1970) geeft een bijzondere dimensie aan het woord maakbaar. Op het eerste gezicht lijkt de keuze van zijn onderwerpen willekeurig, maar na enig rondkijken en wat mentale sprongen openbaart zich een mix van mildkritische houding en diepe betrokkenheid met zowel menselijk als dierlijk leven. Want wat is, op de enorme poeha van de mens na, het verschil nou eigenlijk. De mens pretendeert graag dat het leven maakbaar is. Scherft doet daar wat aan, met omtrekkende bewegingen. Lastig uit te leggen hoe dat werkt, maar stel nou dat de schilderijen ergens in het midden staan, en dat de automata, de papieren vogeltjes en de enorme houtskooltekeningen van al dan niet prehistorische dieren deels dienen als uitvergrotingen, deels als focusverschuiving, en misschien terloops ook wel als dwaalspoor. Het verklaren valt ogenschijnlijk niet moeilijk.

Zie de beboste landschappen, en u realiseert zich moeiteloos dat die singuliere aap in twee meter hoog houtskool getekend, zich hoogstwaarschijnlijk ophoudt in dat geboomte. Met de vogeltjes is dat nog vanzelfsprekender. Maar de automata dan, werpt u vermoedelijk tegen. Luister, viel eerder niet het woord maakbaar? En valt u wellicht op dat men zich graag afvraagt wanneer de robot het mensdom in de tang zal nemen? En, hoe boeiend ook, denkt u bij het zien van een gerobotiseerde Goudleeuwaap, die na het opwinden van het mechaniek voornamelijk zijn wenkbrauwen ophaalt, niet eventueel dat die aap daar gelijk staat te hebben?

Als ik niet beter wist zou ik denken dat Scherft de kunst zelf op de pijnbank legt. Door de grote nadruk op maatschappelijke relevantie, hoe goed bedoeld ook, heeft de kunst zichzelf maakbaar gemaakt, gedwongen in een keurslijf, onttrokken aan het ondoorgrondelijke dat het leven en de kunsten tot nog toe met elkaar gemeen hadden. Scherft huppelt daar schijnbaar lichtvoetig tussendoor, al lijkt het ook alsof hij met de grote houtskooltekeningen zich heeft opgelegd om alles wat groter is dan de mens in een reusachtig boek op ware grootte te catalogiseren. Wat het leven nog steeds niet maakbaar maakt, maar het lichtvoetige in zijn schilderijen, automata en papieren vogels juist accentueert.

Maar heeft de natuur dat nodig, die is van zichzelf toch prachtig, roepen u en ik! Welzeker, vooral als we vergeten dat elke vezel van elk organisme is doortrokken van een eeuwigdurende strijd van overleven, in welke context het schoonheidsbeleven hooguit een kwestie is van pauzevulling. Noemt u mij geen pessimist. Komt een uitbarstende vulkaan - die dat overigens niet doet uit overwegingen van eten en gegeten worden - alleen in aanmerking voor esthetische duiding als hij dat doet ver van de bewoonde wereld? Nog afgezien van het dierenleed, dat zich aan onze waarneming onttrekt, of althans, dat voornamelijk telt naarmate de zichtbaarheid groter is. Hebt u ooit stilgestaan bij de doodsnood van miljoenen salmonellabacterieën als u uw kippeboutje in de pan gooit?

Na een dag met tal van werken uitgepakt om me heen, de meeste nog zonder lijst, begin ik in te zien dat de samenhang veel vanzelfsprekender is dan gedacht. Het ligt er maar aan vanaf welke afstand je naar een dier of een landschap kijkt. Immers, het is toch heel vanzelfsprekend dat al die minutieus geschilderde boompjes op die piepkleine landschapjes zijn bevolkt met dieren, waarvan Johan Scherft er sommige als het ware uitplukt en schildert. Papieren vogels geschilderd? Ja, drie-dimensionaal in papier uitgevoerd, en met olieverf beschilderd. Net als de vier in miniatuur uitgevoerde apentronies. Of getransformeerd tot een automaton, geïsoleerd in een zwarte omgeving, als zodanig ook in papier en olieverf uitgevoerd, maar nu subtiel bewegend. Waarmee bij wijze van spreken het leefritme wordt ingetoomd tot een stilte oproepende vertraging, die zich net zo makkelijk laat vertalen in onder water voortbewegen.

Eenmaal vertrouwd zijnd met het gemak waarmee Scherft dimensies dooreenhusselt, zijn zelfs zijn enorme houtskooltekeningen van dieren, die soms met één been in het heden staan, of juist in de prehistorie, vanzelfsprekend. Ook die vindt u terug in die minutieuze schilderijtjes, weliswaar op schaal, dus dan weer piepklein.

Hoe hartverwarmend is het niet - in een tijd die in het teken staat van digitalisering - dat schilder Johan Scherft zijn fascinatie voor die vliegende wezentjes sublimeert in het maken van papieren vogeltjes, die hij vervolgens tot leven wekt met olieverf. Maar daar stopt het niet. Soms haalt hij een vogeltje weer uit elkaar en maakt er een bouwplaat van. Die bouwplaat digitaliseert hij en zet hij op internet te koop. Die vindt over de hele wereld voor vijf € gretig aftrek. Waarna de kopers zich zetten aan het herscheppen van dat vogeltje.

Als het gelukt is sturen zij hun bevindingen en overwegingen ongevraagd naar Johan Scherft, met een keur van verhalen over wat het vogeltje met hen doet. Waarmee een bijzondere cirkel is gesloten: met het stapje dat het menselijk bewustzijn maakte door het implementeren van het dierenleven in hun eigen menselijke sores. Die dan weer wordt teruggekoppeld ten faveure van het gemaltraiteerde voorbeeld. Hoe veel er ook nog te doen valt, die cirkel is dan toch maar rond.

|

|