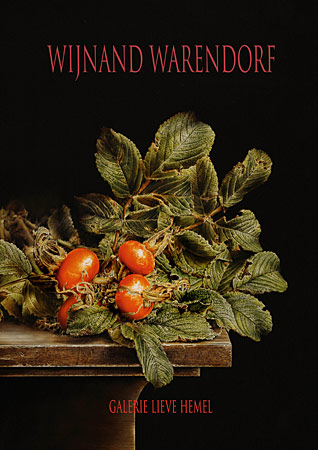

Dans van de Tomaat In 1969, nota bene het eerste bestaansjaar van de galerie, stichtten toneelspelers verwarring met het gooien met tomaten uit protest tegen de vastgeroeste theaterorde. Zoiets hoort thuis in een canon van gebeurtenissen, die invloed hebben gehad op de ontwikkeling van het maatschappelijk bewustzijn, maar hoe dan ook, je zou toch aannemen dat ik, na dit van redelijk nabij meegemaakt te hebben, me door een tomaat niet gauw meer uit het veld laat slaan. Maar nu is Warendorf er toch in geslaagd mij in de war te brengen met zijn tomaten. Voor mijn geestesoog, kijkend naar een foto van zijn schilderij met de console met de tomaten erop, denk ik die console in 3-D tussen de schilderijen te zien hangen, waarop wekelijks verse tomaten worden gelegd. Als offer èn monumentje bij wijze van ode aan de Hollandse kassenbouw, die onder het gedaver van overvliegende passagiersvliegtuigen gebukt gaat onder verkeerde onzelieveheersbeestjes, helaas exoten die zich als alleseters ontpoppen, en ook de Hollandse onzelieveheersbeestjes consumeren, waarmee wij nu het gesprek moeten aangaan. Ook wat dat gesprek betreft zijn de schilderijen van Warendorf onverwacht actueel.Tijdens een kort verblijf in Frankrijk was het me gegund een wesp een stukje ham te gunnen, waarmee hij (of zij) wegvloog, maar niet na een vliegdansje gemaakt te hebben, de ogen gekeerd naar het gezelschap aan tafel. De wesp kwam terug en herhaalde dit ritueel totdat de ham op was. Ik mag me er dus op voorstaan gecommuniceerd te hebben met een wesp, min of meer naar analogie van wat ik eerder in een wetenschapsbijlage had gelezen, dat bijen elkaar door middel van een dans vertellen waar zij honing gevonden hebben. De eerlijkheid gebiedt me toe te geven dat wie een wesp van zich afslaat ook communiceert, maar u begrijpt, ik bedoel vreedzaam en met begrip. En zo kom ik toch weer terug op de tomaten van Warendorf. Meer nog dan de druiven - waardoor weet ik niet, misschien omdat die tomaten in dit geval niet in de meerderheid zijn, en die kom toch minstens evenveel druiven bevat als ik bezoekers op de opening hoop te tellen. Maar ik dwaal af. Die tomaten liggen niet, zij staan. Zij zijn actief aanwezig, zij beïnvloeden het vertrek waarin het schilderij hangt, zij nemen deel aan het gesprek. Ik zou flauw zijn als ik nou ging uitleggen dat ik vooral niet ga uitleggen dat en eventueel waarom Warendorf wel of niet betrokken is bij het milieu, de opwarming van de aarde, de bedreiging van vele diersoorten, en uiteindelijk de mens. Het is volkomen vanzelfsprekend dat het hem beroert, dat hij wil dat het anders was en dat hij, als hij het voor het zeggen had, er iets aan zou doen. Maar zijn tomaten zijn meer dan dat, dus wil ik voorkomen dat het oog en de geest bij het menselijk falen blijven steken, niet over de blokkade van afgedwongen moraal heen kunnen kijken. De tomaat kan best overleven in het wild, sterker nog, dan wordt hij na een tijdje kleiner en smaakvoller. Stel dat de mens zich niet weet te beteugelen en alsnog zoveel rampen voor zijn kiezen krijgt dat de soort op gegeven moment gedecimeerd is, verstoken van enige luxe en het moet doen met wat de tot wildernis verworden habitat hem biedt. De mens zal, mèt de tomaat, kleiner worden, sterker en eventueel smakelijker voor de explosief in soortenrijkdom en talrijkheid gestegen muggen en andere bloed- en of vleesetende insecten, die op hun beurt de mens de beschikking geven over een rijke bron van eiwitten, van diezelfde insecten, en dan vooral hun larven. Maar misschien, heel mischien handhaaft de mens ook zijn tot nog toe verworven geestelijk vermogen, zonder gebruik van zaken die vroeger onder de noemer vooruitgang werden gerangschikt, en neemt hij genoegen met het pure talent te kunnen denken, zonder een spoor van gewin of geweld, en dan zal blijken dat tomaten niet alleen staan, maar ook dansen, de appels zich onttrekken aan de zwaartekracht, de pijnboompitten als mieren marcheren en haren zich vrij voelen te groeien op armen en benen. Dat zelfs tomaten, of althans hun blaadjes en takjes, haren hebben, zal bijdragen aan het ontkrachten van schoonheidsideaal als menselijke drijfveer. Hoewel Warendorf als een bezetene die haartjes schildert, zal hij zich onttrekken aan deze dialoog. Althans, er is altijd onstuitbaarmeer dat zich niet in woorden laat vangen. Zoals een ontkenning altijd meer betekent dan dat het niet waar is. Waaraan wij, de rest van de mensheid, verstandig doen een voorbeeld te nemen in ons doen en laten. Wat minder moeilijk is dan u denkt, want u, ik bedoel, wij kijken toch naar zijn schilderijen, naar de vruchten, de takjes, de haartjes, zonder angst voor de onmetelijke donkere diepte die zich op sommige schilderijen daarachter uitstrekt, die als het ware het onbekende symboliseert, op de voorgrond waarvan wij onbekommerd rond de details van Warendorf dartelen? Net als de rest van de mensheid, die toch ooit zal moeten begrijpen dat het echte inzicht onbereikbaar is, maar dat dat de pret denken niet mag drukken, en zelfs het eindeloos zoeken blijvend zin geeft. Net als de onverklaarbare en niet te stuiten drang van Warendorf om elk haartje op zijn paneel te krijgen. Waarom? Daarom. Dance of the Tomato

It was back in 1969 (which coincidentally, or possibly not so coincidentally, was the year in which Lieve Hemel Gallery burst upon the scene) when drama school students in a protest against the theatrical establishment came up with the idea of pelting actors mid-performance with tomatoes. The Tomato Campaign, as it has since been dubbed, is an example of the sort of event that warrants a mention as part of the canon of events having left their mark on the development of social awareness. It would make sense for me, as a relatively close observer of the upheaval, not to be fazed by a mere love apple … and yet it is this very sense of confusion that Wijnand Warendorf and his tomatoes have instilled in me. As I am looking at a photograph of his painting showing a display of tomatoes, in my mind’s eye the sill on which the tomatoes rest becomes suspended in 3D among the paintings, to receive its weekly offering of freshly picked tomatoes by way of a miniature memorial cum ode to the Dutch horticultural industry, beset as the latter is – while passenger aircrafts continually thunder past overhead – by exotic ladybirds which owing to their evidently omnivorous nature think nothing of cannibalising their indigenous opposite numbers whenever the mood strikes them, and with which we are now having to enter into a dialogue. The dialogue too is an unexpectedly topical aspect of Warendorf’s paintings. When recently I spent a few days in France, I decided to offer a passing wasp a tiny morsel of ham, which the wasp duly accepted and made off with, but not before it had performed a little airborne dance, eyes firmly fixed on the company at the table. The wasp kept returning for more of the same until there was no more ham to be had. I can thus pride myself on having conversed with a wasp, more or less along the lines of the article I once read in the scientific section of a newspaper in which it was explained how bees perform a particular dance to tell each other where there’s honey to be found. Clearly I am referring to peaceful and considerate communication, although I have to admit in all honesty that anyone who shoos away a wasp could by the same token be regarded as engaging in communication of sorts. Which brings me back to Wijnand Warendorf and his tomatoes, more so even than to his grapes, I have no idea why, perhaps because the tomatoes are fewer in numbers and the number of grapes in the bowl is at least similar to the number of visitors I am looking forward to welcoming at the official opening. But let’s not digress. Rather than being prostrate, the tomatoes are actually positioned upright. They have an active presence, they affect the room in which the painting is displayed, they participate in the dialogue. It would be silly for me to launch into an explanation of why I will refrain from explaining that (and possibly even why) Warendorf is or is not concerned about the environment, about global warming, about the threats affecting multiple animal species and, ultimately, mankind itself. It is perfectly obvious that he is concerned with all of this, that he wishes things were different, that he’d do something about it if it were up to him. But his tomatoes are so much more that I owe it to him to ensure that the eye, and the mind, should not get bogged down at the level of human failure. The tomato is perfectly capable of “roughing it”. Over time it will, in fact, gain in flavour what it loses in volume. If man fails to control his urges and ends up being overwhelmed by so many disasters as to cut a swath through the entire human species, strip it of all things fancy and leave it no choice but to make do with what its then dilapidated habitat has to offer, humans – like tomatoes – will eventually become smaller and stronger, as well, quite possibly, as tastier to mosquitoes and other insects that feed on blood and/or flesh, whose diversity in species and sheer numbers the dilapidation of society as we once knew it will have caused to explode and which in turn – not least through their larvae – will have come to represent a rich source of proteins to us humans. Then again there may be a chance – even if it’s just on the off-chance – that mankind may succeed in preserving the mental prowess it has to date secured and, rather than making use of resources that used to be classified under the heading of “progress”, settle for the pure talent that is the capability of thought, without the merest trace of being out for gain or inclined to use force … and it is then that tomatoes will be shown not only to be positioned upright but dance, apples to defy gravity, pine nuts to march like ants and hairs to feel free to grow on arms and legs. T he fact that even tomatoes, or at least their leaves and twigs, boast hairs will contribute to the invalidation of the beauty myth as a driver of human action. Although these tiny hairs too are included in Warendorf’s paintings, the artist will distance himself from the actual dialogue, or rather, there is always something more, something that defies being captured in words, the way a denial by definition is more than a mere statement to the effect that something or other is not true, as a lead the rest of us humans would do well to follow in our actions, which incidentally is not as hard as you might think, for isn’t it true that you look, or rather, that we look at Warendorf’s paintings, at the fruits, the twigs, the hairs, without fear of the immeasurable dark depth that extends beyond in some of his work, in a way as a symbol of the unknown in the foreground of which we blithely flit from one detail to the next? Just like the rest of mankind, which sooner or later will have to accept that genuine insight is unattainable and that this is nothing to worry about, as even the never-ending quest itself can give an air of enduring meaningfulness to their existence – just like Warendorf’s inexplicable, inexorable need for incorporation in his work of every last bit of tomatoey fuzz. Why, you ask? Because, that’s why. |

|

TOP